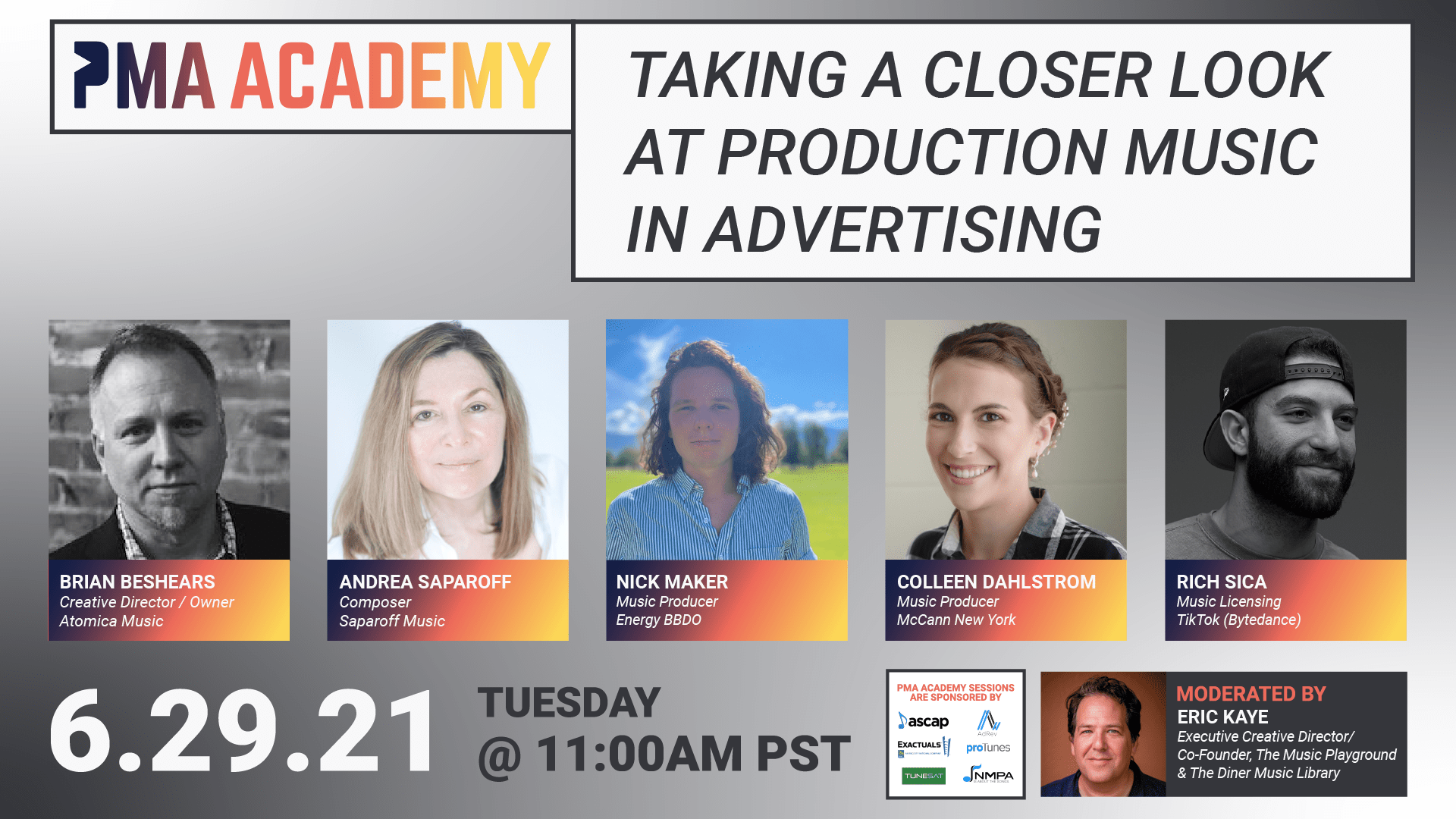

How they recommend libraries and composers approach royalty tracking? What is the best method for composers to learn PRO methods for defining their rates for broadcast television royalties?

As I mentioned on the panel, there are many factors that affect what a particular performance royalty payment will be for any type of use. One first has to look at the license fees being paid to the PRO by a particular media (network tv, cable, streaming services, radio, etc.). These fees are arrived at either via voluntary negotiations with industry wide committees, individual users (broadcasters, streaming services, etc.) or federal rate courts, mandatory arbitrations or other types of dispute resolution procedures.

The number of total performances in a quarter in a particular media also comes into play. In the audio-visual area (broadcast tv, streaming services, cable, etc.), many different factors come into play including Type Of Use (score, visual vocal, background vocal, theme, logo, promo, trailer, jingle, copyrighted arrangement of a public domain work etc.) as all have different values relative to each other. Time of day and audience measurement of the show, duration of the use, history of past performances, whether the composition is eligible for a bonus payment and what type of PRO license the user is paying under (blanket, per-program, carve out/adjustable fee blanket, through to the audience, direct or source, etc.) all come into play in determining a final royalty payment.

Our book, “Music, Money and Success: the Insider’s Guide to Making Money in the Music Industry” (8th edition) contains a 60 page chapter on ASCAP, BMI, GMR and SESAC and goes into detail as to the payment formulas and rates.

As to tracking, there are many companies and systems employing either fingerprint, watermark or other forms of music recognition technology (MRT) including BMAT, Soundmouse, SourceAudio, Shazam, Numerator, Tune Sat, Landmark, Nielsen, Gracenote, Audible Magic and DJ Monitor, among others. A number of these companies are in partnerships with the U.S. PROs helping to track and identify musical compositions on television, radio and other media. It is important to remember that this technology only identifies recorded music. As to each particular PRO, both in the U.S. and in foreign countries, it is best to check directly with them as to what technology and music recognition systems they are currently using.

Keep in mind, correct cue sheets as well as correct registrations are essential in getting paid what you are due. For any type of audio-visual production, cue sheets are always necessary. Digital fingerprinting technology has now also entered into the cue sheet creation process. As to the registration of any work, it is important that you understand each PRO’s requirements needed for a correct registration as the requirements differ based on the type and use of a work. In some cases, only cue sheets are necessary. In others, cue sheets and individual registrations are needed. For example, commercials, movie trailers, promos, infomercials and public service announcements require additional information than is normally the case with other types of uses. Always check with each PRO’s website or staff for up to date registration and other requirements.

With most of the business world embracing technology, why have the PRO’s been slow to adopt a technology that more accurately detects performances of my music around the world?

My understanding is that many of the major PROs around the world are currently using sophisticated tracking systems which are being updated as technology permits. Again, one should check with each PRO as to the technology being utilized.

As terrestrial television is increasingly challenged by streaming and OTT platforms, how can we best ensure composers’ royalties aren’t undermined?

It is important that any new type of user, whether in traditional media or in the online/digital world, have an appreciation of the role that music plays in its productions. In many cases that is evidenced in the license fee negotiations between the user and the PROs and other collection agencies as well as with other copyright owner representatives (music publishers, agents, lawyers and managers, collective bargaining entities, etc.). The producers of audio-visual programming are also important in the equation.

One also has to understand that in the online world (audio and audio-visual streaming services, etc.), there are many trillions of performances occurring and being processed annually as opposed to the much more limited number on broadcast television and cable (of the 5 trillion performances being processed by ASCAP and BMI annually), 98% are digital). Consequently, per performance values vary greatly depending on whether a performance is on a traditional media outlet versus a streaming service. For example, in a recent quarter, 1 network television primetime series theme performance would need in the area of 6 million views on an audio-visual streaming service to equal the same amount of composer or publisher royalty.

It is important to note that as viewership migrates to these AV streaming platforms, their revenues and license fees will grow resulting in increased performance royalties for composers, songwriters and music publishers. In time, these services will most likely eclipse the traditional broadcast model in viewership and as a source of performance royalties . It is critically important that composers strive to retain their performance royalties in their work-for-hire production music agreements during this media transition.

As sampling technology allows for increasingly convincing music production, is there any value in recording real instruments and ensembles or is it simply a waste of money?

Live instruments always improve the quality of any type of recording. Many times, you will see an underlying electronic bed with select live instruments added subsequently. In most cases, it’s a budget consideration.

When providing tracks for library music labels, it seems to be the norm to give up publishing for eternity and the world so when is it legitimate to have an end date or some form of limit depending on the profit made or other? Especially if there is no upfront fee paid for the track?

As was discussed on the panel, in “work for hire agreements”-whether they occur in the production music area, feature film or episodic television area, the actual creator of a work is not the legal “author” of the work. The employer/buyer/company becomes the author and exclusive owner of all rights under the U.S. Copyright Law. There is no termination of copyright ownership right for the territory of the U.S. if a composition is a work-for-hire.

Is it realistic for a lesser known composer writing for a music library to ask them to pitch in for lawyers fees?

Under the heading, “I suppose anything is possible in a negotiation depending on bargaining power”.

“Company shall pay composer 50% of net receipts received by company prorated by composer’s respective writer’s share”? I am curious what the term “prorated” means in this sense?

The term “prorated” has to do if multiple writers are involved in a composition. For example, if the net receipts 100% writer amount came to $100. and there were 2 equal writers on a composition, each would receive $50. If there were 3 writers, each would receive $33.33 each.

If you are registered with BMI, is that enough? Should one also register with SoundExchange? How do these entities work together or not?

ASCAP, BMI, GMR and SESAC are performing rights organizations (PROs) which license users (radio, broadcast television and cable, streaming services, bars, concert halls, universities, etc.) for any type of music use (audio, audio-visual, etc.). Songwriters, Composers and Music Publishers join or affiliate with these PROs for representation. This right of Copyright is known as the Performance Right and involves the underlying musical composition.

SoundExchange involves a limited performance right in Sound Recordings. This a statutory license created by Congress and applies primarily to non-interactive sound recording performances on satellite radio, (SiriusXM), Pandora and other non-interactive streaming services, the audio only music channels on cable television (Music Choice) and certain business establishment audio music services (Muzak, DMX, etc.) It is an AUDIO only right and has nothing to do with any audio-visual presentation or download. SoundExchange is the sole entity designated by the Copyright Royalty Board to collect royalties paid by services operating under the statutory license.

Record companies, recording artists and background singers and musicians register with SoundExchange and all royalties are split 50% to the sound recording copyright owner (the label, normally), 45% to the featured artist and 2.5% each to background musicians and vocalists on any recording. SoundExchange collected 963 million dollars in 2019 and distributed $908 million dollars and has become a major source of income for creators. As there is no fee to register, anyone involved in any type of recording should join SoundExchange.

What do you think the percentage of production music songs actually get used?

There are many entities these days providing production music in its many forms. As the majority of this recorded music is already pre-cleared for both the musical composition and master recording, you literally have a “universe” to choose from – a universe that is continually expanding with new offerings. Based on the increasing quality of the music and recording as well as the diversity of composition, the use of production music has increased substantially over the years.

Would you be willing to share the document with the survey data you compiled on ranges of rates for different uses, media type and number of plays?

Basically I mentioned figures during the webinar as examples of some recent years PRO royalties for certain types of uses-score, themes and feature performances- on network primetime television (normally the highest paying uses in my experience) as well as various basic and pay cable systems and audio-visual streaming services. As I mentioned previously, there are many factors that affect the value of any type of performance starting initially with the license fees negotiated for that media and the specific payment formulas of each PRO for a particular type of use (keep in mind, that the 4 U.S. PROs have entirely different payment formulas and payments for every type of use and media).

In order to illustrate the importance in any royalty formula of the license fees negotiated for a particular area, I used an example of 1 minute of score for a primetime network tv show, a pay cable channel, a basic cable movie channel and an audio-visual streaming service. Based on the many factors involved in determining values, the composer or publisher royalty ranged from $120-$225 for the network example, $20-$40 for the pay cable channel, $3-$5 for low end movie channel. For the streaming service, I had $18 for 1 million views. These numbers are for illustration purposes only as many factors can either raise or lower these numbers. The point being, where a program airs is the starting point of the royalty equation.

A production music library wants 50% writers share…is it worth it? So hard to find work, it’s hard to say no these days.

As I stated during the webinar, I have always taken the position during my entire career that a writer’s share should only be attributed to the writer as well as any other collaborating influence or participant.

Comments by Todd Brabec – 7/6/20

* The comments and opinions expressed above are those of Todd Brabec alone.

* For more information on film, television, video game and production music scoring and writing original songs contract clauses referred to in the webinar, see the Television, Motion Pictures and Video game chapters in the 8th edition of “Music, Money and Success”.